The Typewriter

|

| Popular Mechanics/Spencer Jones |

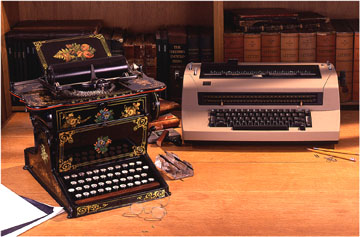

The 120-year-old qwerty-keyboard typewriter revolutionized the world of communications and still hammers out a lasting mark.

- By Darryl Rehr

- PM Photo by Spencer Jones

Origionally published in August 1996 by Popular Mechanics,

reprinted here by the author's permission.

The sounds of the marvelous old manual typewriter echo through the dimly lit room. Pounding the keys with heavy hands is a writer who is hardly in the process of creating the Great American Novel, but there is no doubt that he's using a Great American Machine, which is putting some real muscle into his prose. If he were using a modern word processor, would it feel the same?

The typewriter is one of America's great unsung inventions. While the telephone, automobile and airplane sped up communications and transportation, the typewriter did the same thing for the written word. But few people paid much attention, possibly because they were too busy reading what the typewriter had written about all the other headline grabbers.

| Typewriter Timeline

Click on the image for more info. |

|

The story of the typewriter begins in 1868, when a multitalented tinkerer named Christopher Latham Sholes came up with a crude writing machine in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Five years later, an improved version was presented to E. Remington & Sons, of Ilion, New York, and in 1874 the first Sholes & Glidden Type Writer came out of Remington's factory. (Carlos Glidden was an associate of Sholes' who had helped in the initial development.)

The machine was a real beauty–elaborately decorated with colorful flowers and golden curlicues. It sat on a stand and used a foot pedal for a carriage return. As strange as this model may look to us today, it is unmistakably a typewriter, and it would be almost 90 years before the basic concept developed by Sholes would substantially change.

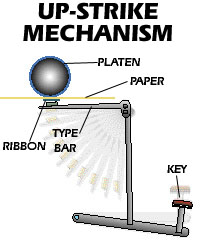

The fundamental mechanism that made the Sholes machine work was a circular arrangement of type bars, which are rods with printing types attached to the heads. The type bars hung in a downward position and were linked by wires to the keys. When a key was pressed, a type bar swung upward and its head hit an inked ribbon against a cylindrical platen.

The chief difference between the Sholes machine and modern models is that the up-strike mechanism kept the typed sheet of paper hidden from view. kept the typed sheet of paper hidden from view. As a result, these machines were known as blind writers, and users had to lift up a hinged carriage to see the tiny, capital-letters-only typing on the paper.

At $125 each, the Sholes & Glidden was an expensive piece of office equipment, nearly $1400 in the currency of 1996, and initially sales were dismal. In its five years of production, just 5000 units were sold. Still, the machine had many supporters.

Among the first was Mark Twain, who bought a typewriter the moment he saw one. Twain only played with the machine, and never used it to do any writing. Instead, he paid professional typists to transcribe his manuscripts, and so became the first author to send a novel (Life On The Mississippi in 1883) to a publisher in typed form. Years earlier, however, Victorian actress Fanny Kemble used her Sholes & Glidden to crank out copy for a column in Atlantic Monthly, which gives her the distinction of being the first known writer to use a typewriter.

|

| The qwerty keyboard (above) is still the standard today, even in the age of computers. Competitive designs have appeared through the years, including the Blickensderfer Scientific keyboard, but none was successful. |

|

If there's one thing that links the first typewriter to nearly all of its descendants (including computers), it's the qwerty keyboard, which takes its name from the first six letters, from left to right, in the top row of letter keys. Sholes developed this arrangement and took a lot of heat over the years from competitors who spread the false rumor that he intentionally created a confusing keyboard to slow down fast typists who would otherwise jam his clumsy machine.

In fact, the qwerty keyboard was designed to solve jamming problems and improve typing speed. During the design process, Sholes realized that jams occurred only when two adjacent type bars were activated one after another. To solve the problem, he took the most frequently occurring letter pairs (such as th and ed) and arranged them inside the machine so none would be adjacent. While jamming might still occur, it would happen less frequently and typists, therefore, could go as fast as possible. The qwerty layout came about when Sholes simply connected all the wires to the keys after the inside arrangement had been made.

By being first out of the box with qwerty, Sholes and Remington set a standard that became unstoppable. Many other keyboards have been tried over the years, including the Blickensderfer Scientific and the Dvorak, but none has taken hold.

The clumsy, all-caps Sholes & Glidden machine struggled through five years of production and was succeeded by the Remington No. 2 in 1878. This machine set the mold for the next 50 years, creating the black, open-framed look that most people associate with antique typewriters. This unit had the first shift key for creating upper- and lowercase typing. It was also tough, durable, reliable and, most importantly, successful. The golden age of typewriters had begun.

As Remington quickly took the lead in the new industry, hundreds of competitors jumped in. They all faced a common problem: coming up with a machine that didn't infringe on any of Remington's or anyone else's patents. The result was the production of some very strange writing machines.

|

| The essential breakthrough was the up-strike mechanism. Pressing down on a key forced a type bar to swing upward and hit a platen. By inserting a ribbon and paper between the two elements, machine produced writing was created. |

Typewriters soon appeared with type bars, type wheels, type strips and type shuttles, all before the end of the 19th century. There were single keyboards with shift keys for capital letters, and double keyboards with separate keys for each character. Keys were arranged in straight rows, graceful curves, even full circles. Some typewriters did away with keyboards entirely. Nothing was sacred.

Then, in 1895, a ribbon maker named John Thomas Underwood went to Remington to renew his supplier's contract. Remington showed him the door, saying the company intended to make its own ribbons. Angry, Underwood bought the rights to a new kind of machine, one that typed from the front and actually allowed users to see what was typed on the page.

This visible-writing Underwood No. 5 took the industry by storm, and compelled everyone else to play catch up. By 1908, every other major typewriter maker had switched to the visible format. Other familiar features had also become standardized by this time, such as the 4-row keyboard and the shift key for caps. Still, these improved typewriters were just a variation of Sholes' basic idea. Even most electric typewriters were simply powered versions of a familiar machine.

It wasn't until 1960 that a new standard was set in typewriter design. This was the year the IBM Selectric first appeared. What made the IBM Selectric so successful was its single-element mechanism-a type ball that replaced all the individual type bars. Interestingly, single-element mechanisms had originally appeared in the 1880s on several popular machines manufactured by Hammond, Blickensderfer and Crandall, among others. Blickensderfer, in fact, was also a pioneer in adapting typewriters to electricity, and the Blick Electric of 1902 was an electric typewriter that also incorporated a single-element concept, the same setup perfected in the Selectric nearly six decades later.

Like the Remington-made Sholes & Glidden and Underwood No. 5 before it, the IBM Selectric set a standard that continued for years. But in 1978, a unit appeared that broke the mold again. It was the first electronic typewriter, the Exxon QYX, which used a microprocessor and a daisy-wheel typing mechanism, and this little-known unit set a standard that continues to this day.

With the advent of the computer age, there's no denying that the typewriter has finally been surpassed, although it's true that many people still use them to type preprinted forms and the like. The computer age, coupled with events like last year's bankruptcy of the Smith-Corona company, has made many old typewriters highly collectible, with prices starting at less than $50 for common units and rising to more than $5000.

Naturally, the original Sholes & Glidden model is a prized machine. Values range from $1000 for a black-painted unit to $2500 for an ornamented one and $5000 for an ornamented machine complete with its original treadle table.

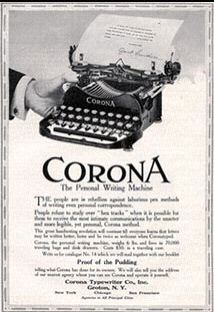

A more common machine, which is still full of old-fashioned personality, is the petite folding Corona. This unit, which was the first successful type-bar portable typewriter, was so popular in its day that 700,000 were made between 1910 and 1940. Today, you can probably find one for about $30. A comparably priced collectible is the unique Oliver, from 1895, which is characterized by a double bank of type bars that swing down from each side. Early Underwood No. 5s can be found for less than $50. A single-element Hammond or Blickensderfer may be worth as much as $100, and a highly ornate Crandall from 1884 can fetch as much as $1000.

Generally speaking, the further removed from the standard Underwood-type machine, a category that also includes most models by Royal and Smith-Corona, the more likely it is to be valuable. For example, typewriters without keyboards, called index machines, are especially desirable to collectors. These unsuccessful designs were the bargain-basement machines of their era, but today they are worth from $100 to $1000.

Other products may have stolen the spotlight from the typewriter since its introduction, but few have been as influential and enduring.